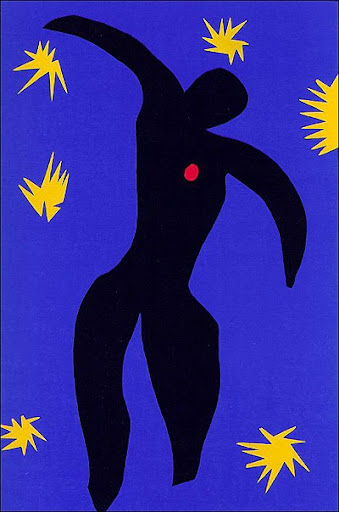

crystal skull, british museum

let's face it, fellow visual artists: digital fabrication is one of many upcoming technological developments that will shake the paradigms of art...without changing the essence of art, but with farreaching consequences for artists' practice, income, distribution etcetera.

will these technological developments help us? i should say so, on many levels. but i see drawbacks too. these drawbacks have to do especially with what i perceive as the proliferating superficiality of `professional' imagery. some possible reasons for this that i see are:

- new technology brings previously difficult to master technical "visual art" effects into the reach of everyone. this encourages people to produce many otherwise shallow images with these effects, where previously these types of images were only produced by artists with a deep technical but also deep artistic development.

- the new (digital) generation of professional imagery-makers for the general public (advertisements, video clips, movies) pays more attention to the technological effects, than to the deepening of the imagery itself. therefore the images are often of a shaming cliché nature, covered by a predictable sauce of technical/digital effects.

- superficial doll-like `perfection', in other words, to cover mediocre visual ideas. a nice(?) example of this is the absolutely ridiculous `crystal skull' which is used in the latest indiana jones movie (indiana jones and the kingdom of the crystal skull). the thing is so obviously made out of some sort of plastic, it is truly amazing that a movie with such a budget for digital/technical effects cannot even achieve anything close to a crystal skull. and, even more ominous, few seems to notice...! although: see here [it is interesting to note that there are hardly any pictures on the internet of the skull-prop used, it seems the movie company is aware of the fakeness the prop radiates. wouldn't it be interesting if in the meantime they had a crystal skull made...to counter further criticism. it also strikes me that digital fabrication would be a nice way to produce such a fake-looking skull from real crystal...] and oh yes, another interesting thing: there are many `old' crystal skulls in archeology...so far all have been found to be 19th/20th century fakes, as far as i can make out from the internet. at least they look like they're made of crystal - probably because they are.

well, in order not to become too pessimistic, even with the above drawbacks, i can see some sort of parallel with the music world. if digital fabrication becomes widespread reality, then artists will have more ways to realize their ideas, more ways to develop their art. also, the artworks themselves become reproducible, bringing them into the home of anyone wishing to pay a modest sum for the digital blueprint (or copying the blueprint from a friend...).

will my house not become overfull? will any visual artist be able to still generate enough income? will the market be swamped by mona lisas, davids, jeff koons's [wow, these are easy to produce yourself, just click `enlarge' on the blueprint of your home china figurines]? i don't know.

i just wish i had a digital fabricator the size of a large barn...but i will settle for a digital painting machine / paintprinter (yes, a machine that really paints, but which is controlled digitally, although i would definitely need a paintpad / digital canvas and a digital brush, perhaps even real paint, i don't know how to solve the kinesthetic problems).